Endocrine hyper- and hypofunction

Endocrine diseases stem from imbalances in hormone levels. Hormone imbalances can affect your pet’s health in many ways. Although some endocrine disorders are not life threatening, many are fatal if not diagnosed and treated.

Diseases can develop because an endocrine gland itself is faulty or because the control of that gland is faulty (i.e., a problem in the pituitary can harm the adrenal glands). Endocrine diseases develop when the body produces too much hormone (hyper- diseases) or too little hormone (hypo-diseases).

A tumor or other abnormal tissue in an endocrine gland often causes it to produce too much hormone. Hormone excess disorders often begin with the prefix “hyper.” For example, in hyperthyroidism, the thyroid gland produces too much thyroid hormone.

When an endocrine gland is destroyed, removed, or just stops working, not enough hormone is produced. Hormone deficiency disorders often begin with the prefix “hypo.” For example, in hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormone.

Treating endocrine system disease

Endocrine diseases caused by too much of a hormone can be treated surgically (tumor removal), with radiotherapy (such as the use of radioactive iodine to destroy an overactive thyroid gland), or with medications used to block the tumor from over-secreting the hormone.

One can normally treat hormone deficiency syndromes simply by supplementing the missing hormone. For example, one can treat diabetes mellitus by giving insulin injections. Steroid and thyroid hormone replacements can usually be given orally. Dogs and cats taking hormone replacement therapy must be monitored for side effects and periodically retested to make sure the drug dosage is correct. In some cases, such as after an endocrine tumor is surgically removed, the remaining gland will recover and hormone replacement will no longer be needed. Unfortunately, most of these treatments are life-long.

1. Diabetes insipidus

Despite its name, diabetes insipidus is not related to the more commonly known diabetes mellitus, and it does not involve insulin or sugar metabolism. The name comes from Greek, where it is roughly translated to mean the “excessive discharge of bland urine.” This is in contrast to diabetes mellitus, which can be translates as the “excessive discharge of sweet urine.”

Diabetes insipidus is caused by problems with antidiuretic hormone (ADH or vasopressin), a pituitary gland hormone responsible for maintaining the correct level of fluid in the body. Either the pituitary gland does not secrete enough of this hormone (called central diabetes insipidus), or the kidneys do not respond normally to the hormone (called nephrogenic diabetes insipidus).

Affected dogs urinate in large volumes and drink equally large amounts of water. The urine is very dilute even if the animal is deprived of water (normally, urine becomes more concentrated when an animal is dehydrated).

Increased urination may be controlled using desmopressin acetate, a drug that acts in a way similar to antidiuretic hormone. Water should not be restricted. Treatment is usually life-long.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about diabetes insipidus on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about diabetes insipidus on our blog for veterinary professionals

2. Pituitary dwarfism (growth hormone deficiency)

In pituitary dwarfism, the front portion of the pituitary gland does not fully develop or is disrupted by a large pituitary cyst. This can lead to deficient secretion of a number of pituitary hormones; including growth hormone (GH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

Pituitary dwarfism is most common in German Shepherds and has been seen in the Spitz, Miniature Pinscher, and Karelian Bear Dog. It is an inherited condition and occurs equally often in both sexes.

The lack of GH is most common and dwarfs the young animal. If TSH or ACTH secretion are also deficient, the blood levels of thyroid hormones and cortisol will be reduced, and the thyroid and adrenal glands will show signs of deterioration. Affected dogs have a shortened life span.

Dwarf pups appear the same as their normal littermates until about 2 months of age. After that, they grow more slowly than their littermates and keep their puppy coat. Primary guard hairs do not develop. Hair is gradually lost on both sides of the body, and truncal hair loss often becomes complete except for the head and tufts of hair on the legs. Permanent teeth do not come in, or come in late. Closure of the growing ends of the bones can be delayed as long as 4 years. The testes and penis of male dogs are small. In female dogs, heat cycles are irregular or absent.

Unfortunately, there is no adequate therapy for pituitary dwarfism in dogs. Canine growth hormone is not yet available for therapeutic use; the only available treatments are porcine (pig) and human growth hormones. However, canine and human growth hormones are different enough that dogs develop antibodies against human growth hormone. This renders the treatment ineffective. Porcine growth hormone works better for treating dogs with pituitary dwarfism, but it is expensive and not widely available.

If growth hormone treatment is undertaken, it consists of subcutaneous injections administered three times weekly for 4 to 6 weeks. Side effects, such as development of diabetes mellitus, are not uncommon. Because the dog’s growth plates in the long bones have already closed, the dog will not grow significantly. However, the dog will likely regrow the primary hair coat. Finally, one should initiate daily thyroid hormone replacement if there is evidence of secondary hypothyroidism.

The long-term prognosis for dogs with pituitary dwarfism is poor if untreated. By 3 to 5 years of age, affected dogs are usually bald, thin, mentally dull, and lethargic. These changes result because the dog is progressively losing pituitary function and the pituitary cysts is continuing to expand.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

3. Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is the condition where the thyroid gland does not produce enough of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. When levels of these hormones are low, it slows the metabolic rate leading to a number of clinical signs.

More than 95% of clinical cases of hypothyroidism in dogs come about from damage to the thyroid gland itself (primary hypothyroidism). At least half of primary hypothyroid cases are the result of autoimmune destruction of the thyroid gland. The remaining hypothyroid dogs have marked shrinkage (atrophy) of the thyroid but no inflammation; most experts believe that thyroid atrophy actually represents the end result of earlier immune-mediated destruction.

The most common cause of secondary hypothyroidism in dogs is a tumor of the pituitary gland, which usually causes deficiencies of other pituitary hormones as well. This is a rare cause of hypothyroidism, accounting for less than 5% of cases.

Hypothyroidism is most common in dogs 4 to 10 years old. It usually affects mid- to large-size breeds and is rare in toy and miniature breeds. Breeds most commonly affected include the Golden Retriever, Doberman Pinscher, Irish Setter, Miniature Schnauzer, Dachshund, Cocker Spaniel, and Airedale Terrier. Hypothyroidism occurs equally in both males and females.

Because thyroid hormone affects the function of all organ systems, signs of hypothyroidism vary. Most signs are directly related to a slowing metabolism, which results in lethargy, unwillingness or inability to exercise, and weight gain without an increase in appetite.

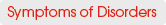

Changes in the skin and coat are common, including dryness, excessive shedding, delayed regrowth of hair, and hair thinning or hair loss (usually the same pattern on both sides), sometimes with increased pigmentation. In more severe cases, the skin can “thicken,” especially on the forehead and face, resulting in a puffy appearance and thickened skin folds above the eyes. This puffiness, together with slight drooping of the upper eyelid, gives some dogs a “tragic” facial expression called myxedema.

Unneutered/unspayed hypothyroid dogs may experience various reproductive disturbances. Females may have irregular or no heat cycles and become infertile, or litter survival may be poor. Males may have low libido, small testicles, low sperm count, or infertility.

During the fetal period and in the first few months of life, thyroid hormones are crucial for growth and development of the skeleton and central nervous system. Dog that are born with thyroid deficiency or that develop it early in life often show dwarfism and impaired mental development. They may also develop a large thyroid gland (goiter), depending on what is causing the hypothyroidism.

To accurately diagnose hypothyroidism, one must first closely evaluate the dog’s clinical signs and routine laboratory tests to rule out other diseases that affect thyroid hormone testing. The veterinarian must confirm the diagnosis using one more specific thyroid function tests. These tests may include serum total T4, free T4, or TSH levels. In some cases, a TSH stimulation test or thyroid imaging (scintigraphy) is necessary for diagnosis.

We treat hypothyroidism by replacing the missing thyroid hormone with synthetic levothyroxine (L-T4). Usually, it takes 4 to 8 weeks of treatment before the coat and body will improve substantially. We also monitor the blood T4 levels during treatment and adjust the daily dose as needed. Once we have determined the appropriate dose, thyroid hormone levels are checked once or twice a year. Treatment is generally life-long, but the prognosis is excellent.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypothyroidism on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypothyroidism on our blog for veterinary professionals

4. Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is a disorder in which the blood levels of thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, are too high. In both dogs and cats, hyperthyroidism is caused by a tumor of the thyroid gland that produces the excess thyroid hormone. Signs reflect increased metabolism, including weight loss, increased appetite, and increased heart rate.

Hyperthyroidism is a rare disorder in dogs. Unfortunately, in contrast to cats, where this disease is generally benign, most dogs with hyperthyroidism have thyroid cancer. Therefore, the first step in the workup of dogs with hyperthyroidism is to take a chest x-ray and biopsy to exclude a malignant tumor.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hyperthyroidism on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hyperthyroidism on our blog for veterinary professionals

5. Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia is an abnormally high level of calcium in the blood. The signs associated with this condition depend on how high the calcium level is, how quickly it develops, and how long it lasts. The most common signs are increased thirst and urination. As the disease progresses, signs may include reduced appetite, vomiting, constipation, weakness, depression, muscle twitching, and seizures.

In dogs, hypercalcemia is often associated with a variety of malignant tumors, an underactive adrenal gland (Addison’s disease), or kidney disease. Less common causes include an overactive parathyroid gland (hyperparathyroidism), vitamin D overdose, and granulomatous disease.

Hypercalcemia is treated by identifying and treating the condition that is causing it. However, the cause may not always be apparent. Supportive therapy, including fluids, diuretics (“water pills”), sodium bicarbonate, and glucocorticoids, is often needed to lower the level of calcium in the blood and stabilize the dog.

Causes and Treatment for Increased Blood Calcium Levels (Hypercalcemia) in Dogs

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypercalcemia on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypercalcemia on our blog for veterinary professionals

6. Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is an abnormally low level of calcium in the blood. The most common causes of hypocalcemia in dogs include previous surgical removal of the parathyroid glands (leading to hypoparathyroidism), kidney disease or failure, and calcium imbalance in nursing females.

Hypoparathyroidism is characterized by low blood calcium, high phosphate, and low parathyroid hormone concentrations. It is uncommon in dogs, but can be caused by previous removal of the parathyroid glands as a treatment for hyperthyroidism or for a parathyroid tumor. Hypocalcemia causes the major signs of hypoparathyroidism by increasing the sensitivity, or excitability, of the nervous system. Common signs include muscle tremors and twitches, muscle contraction, and generalized convulsions.

Diagnosis of hypoparathyroidism is based on history, clinical signs, low blood calcium, high phosphorous, and low serum parathyroid hormone levels. We must also rule out other causes of hypocalcemia.

For hypoparathyroidism and other causes of symptomatic hypocalcemia, the goal of treatment is to normalize the blood calcium level and to eliminate the underlying cause of the hypocalcemia. If an animal is having muscle spasms or seizures because of low calcium levels, immediate treatment with intravenous calcium is needed. Dietary supplements of calcium, often along with vitamin D, are prescribed long-term.

Chronic kidney failure is probably the most common cause of hypocalcemia. However, the hypocalcemia that occurs with kidney failure does not cause the nervous system signs (e.g., muscle tremors and twitches) that are seen in hypoparathyroidism. Treatment in this situation usually involves dietary restriction and therapy to lower the blood’s phosphate concentration.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypocalcemia on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypocalcemia on our blog for veterinary professionals

7. Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus (often called simply diabetes) is a disorder in which the level of sugar in the blood is too high. In dogs, it is usually caused by a deficiency of the hormone insulin.

During digestion, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose (a simple sugar), which is absorbed into the bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, glucose must enter the body’s cells in order to be used for energy. Insulin signals the body’s cells to absorb glucose from the blood.

A lack of insulin (or insulin resistance) creates two dangerous conditions. First, the body’s cells cannot absorb glucose without insulin; they begin to starve despite the abundant glucose. Second, because the body’s cells do not absorb glucose, the blood glucose level remains dangerously high. This excess glucose is eventually excreted from the body through the kidneys. As the glucose passes through the kidneys into the urine, it pulls water with it by diffusion. This causes increased urination, which leads to increased thirst.

Meanwhile, the excess glucose circulating in the bloodstream can have harmful effects as well, including development of cataracts, pancreatitis, and skin and urinary tract infections. With its cells starving for energy, the body begins to break down its protein, stored starches, and fat. In severe diabetes, muscle is broken down, carbohydrate stores are used up, and weakness and weight loss occur. As fat is broken down, substances called ketones are released into the bloodstream where they can eventually cause diabetic ketoacidosis, a severe complication of unregulated diabetes.

Diabetes most commonly affects middle-aged dogs. Large breed dogs and females are more susceptible to developing the disease. Diabetes often develops gradually, and owners may not notice the signs during the initial stage of the disease. Common signs include increased thirst and urination, increased appetite, and weight loss. Diabetic animals often develop chronic or recurrent infections. Dogs with poorly controlled diabetes often develop cataracts, which commonly leads to blindness.

A diagnosis of diabetes mellitus is based on finding high levels of sugar in the blood and urine.

To successfully manage diabetes, you must understand the disease and take daily care of your dog. Treatment involves a combination of weight loss (if obese), diet, and insulin injections generally twice daily. Usually after being diagnosed with diabetes, dogs are hospitalized for a day or two, and multiple blood samples are taken to measure the blood sugar level throughout the day. This information is used to determine the amount and timing of your pet’s meals and the dosage and timing of insulin injections. After this initial stabilization, your veterinarian will provide appropriate instructions on managing this regimen at home. Periodic reevaluation is necessary to ensure that the disease is being controlled. Based on these reevaluations, you may have to change your dog’s treatment regimen over time.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about diabetes mellitus on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about diabetes mellitus on our blog for veterinary professionals

8. Pancreatic insulin-secreting tumor (insulinoma)

An insulinoma is a tumor of the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas (i.e., the pancreatic islet cells). It secretes insulin in large volumes, and is most common in middle-aged to older dogs.

Excess insulin secretion produces low blood sugar concentrations (hypoglycemia). Initially, signs may include weakness, fatigue after exercise, muscle twitching, lack of coordination, confusion, and changes of temperament. Affected dogs are easily agitated, occasionally becoming excited and restless. When hypoglycemia is severe, periodic seizures may occur. A dog might also collapse, appearing to have fainted.

Clinical signs occur only infrequently when the disease first begins. However, they become more frequent and last longer as the disease progresses. Attacks may be brought on by exercise, by fasting, or by eating (which can stimulate the tumor to release more insulin, lowering blood sugar levels further). Signs resolve quickly after glucose treatment. Repeated episodes of prolonged and severe low blood sugar can result in irreversible brain damage.

Diagnosis is based on a history of periodic weakness, collapse, or seizures, along with tests indicating low blood sugar.

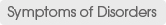

Removing the tumor surgically can correct the low blood sugar and nervous system signs unless permanent brain damage has already occurred. However, if the tumor has already spread (metastasis is common), blood sugar levels may remain low after surgery. Unfortunately, insulinomas are often malignant, and affected dogs often live only around a year. We can often improve these dogs’ quality of life by modifying their diet and administering medications to increase their blood glucose level.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about insulinoma on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about insulinoma on our blog for veterinary professionals

9. Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

Cushing’s syndrome, also called hyperadrenocorticism, is chronic excess of an adrenal cortex hormone, cortisol. It is a common endocrine disease in middle-aged and older dogs. Miniature Poodles, Dachshunds, Boxers, Boston Terriers, and Beagles are particularly vulnerable.

There are three major causes for Cushing’s syndrome. The most common cause (85–90% of cases) is a tumor in the pituitary gland. The pituitary tumor produces a hormone (ACTH) that causes the adrenal gland to grow and oversecrete cortisol. Less commonly (10–15% of cases), the adrenal glands themselves develop a cortisol-secreting tumor. Long-term use of corticosteroid drugs (prednisone, dexamethasone, etc.) used to decrease inflammation or treat an immune disorder is a common cause of Cushing’s syndrome.

Common clinical signs include increased thirst and urination, increased appetite, heat intolerance, lethargy, a “pot belly,” panting, obesity, weakness, thin skin, hair loss, and bruising. Rarely, calcinosis cutis develops, a condition in which minerals are deposited in the skin and can appear as small, thickened “dots” on the abdomen.

Diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome can be difficult. Laboratory test results may be inconclusive and dogs suffering from other diseases commonly show false-positive test results for Cushing’s syndrome. However, once we have diagnosed Cushing’s syndrome, the next step is to determine whether the disease stems from a tumor of the pituitary or of the adrenal. This can be done by further endocrine testing or by imaging techniques such as abdominal ultrasound.

Most dogs with hyperadrenocorticism can be treated with drugs such as mitotane (Lysodren™) or trilostane (Vetoryl™). However, these drugs are most safe and effective when used under the supervision of a veterinarian with much experience their use. If the dog has a tumor of the adrenal gland, surgical removal is generally the best option. Finally, external radiation therapy can help dogs with pituitary tumors, especially large ones.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about Cushing's syndrome on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hyperadrenocorticism on our blog for veterinary professionals

10. Atypical Cushing’s (adrenal sex steroid excess)

Atypical Cushing’s syndrome is a disorder of dogs that remains incompletely understood. These dogs show many of the classic features of typical Cushing’s syndrome. However, dogs with atypical Cushing’s syndrome show normal or borderline cortisol levels on standard endocrine testing. To make understanding this confusing disorder even more complex, atypical Cushing’s syndrome may also be referred to by other names, including the adrenal hyperplasia-like syndrome, pseudo-Cushing’s, or Alopecia X.

A theory has arisen that the clinical signs of atypical hyperadrenocorticism result from excess adrenal secretion of sex hormones rather than cortisol. These adrenal sex steroids include both androgens (i.e., hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione) and estrogens (i.e., estradiaol). In many of these dogs, blood levels of one or more of the ”adrenal sex steroids” are high. Most veterinarians consider high adrenal sex steroid levels diagnostic for atypical Cushing’s syndrome.

Dogs with this atypical disorder generally respond to drugs like mitotane or trilostane, similar to dogs with typical or classical Cushing's disease. Some reports suggest that melatonin and flax seed oil may also be effective in some dogs with this disorder.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

11. Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism)

Addison’s disease, also called hypoadrenocorticism, is a disorder in which the adrenal gland (adrenal cortex) does not produce sufficient hormones. It is most common in young to middle-aged dogs.

In most cases, we cannot determine what caused the adrenal disease. However, most dogs appear to have an autoimmune condition in which the body destroys part of the adrenal cortex. Rarely, infiltrative conditions such as cancer can metastasis to and destroy the adrenal gland to cause Addison’s disease. Finally, treatment of Cushing’s disease with the drugs mitotane and trilostane can result in complete adrenal destruction and Addison’s disease in some dogs.

With complete adrenocortical destruction, the dog develops both cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies. Aldosterone is the main mineralocorticoid hormone, and it affects the levels of potassium, sodium, and chloride in the blood. Low levels of aldosterone cause potassium to gradually build up in the blood and, in severe cases, cause the heart to slow down or beat irregularly. Some dogs have such a slow heart rate (50 beats per minute or lower) that they can become weak or go into shock.

Some dogs have “atypical” Addison’s disease. They are only deficient in cortisol and maintain a normal aldosterone level, at least early in the course of their disease. These dogs are more difficult to diagnose because their signs are milder and the serum potassium, sodium, and chloride values all remain normal.

Signs of Addison’s disease include repeated episodes of vomiting and diarrhea, loss of appetite, dehydration, and gradual, but severe, weight loss. Because the clinical signs of Addison’s disease are vague and nonspecific, it can be difficult to diagnose in the earlier stages of disease. Therefore, severe consequences, such as shock and evidence of kidney failure, can develop suddenly in some dogs.

A veterinarian may suspect Addison’s disease based on the dog’s history, clinical signs, and certain laboratory abnormalities, such as low serum sodium and high potassium concentrations. However, one must specifically evaluate adrenal function to definitively diagnose Addison’s disease.

To evaluate adrenal function in dogs with suspected Addison’s disease, we collect a blood sample to measure the level of cortisol. We then administer a dose of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). After an hour, we collect a second blood sample to measure cortisol again. In healthy dogs, the baseline cortisol concentration is normal, and ACTH will stimulate the adrenal gland to secrete cortisol, In contrast, dogs with Addison’s disease have a low baseline cortisol concentration (before we administer the ACTH) and show little or no rise in the cortisol value after the ACTH injection.

Untreated, Addison’s disease can lead to an adrenal crisis. An adrenal crisis is a medical emergency that requires intravenous fluids to restore the body’s levels of fluids, salts, and sugar to normal. Once stabilized, the dog can then be treated with hormone replacement therapy (either orally or by injection). With proper treatment, the long-term prognosis is excellent.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about Addison's disease on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypoadrenocorticism on our blog for veterinary professionals

12. Pheochromocytoma

Pheochromocytomas is a tumor of the adrenal medulla that secretes epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline), or both. Often, there are no clinical signs, and the tumor is found by chance while performing an abdominal ultrasound for the workup for an unrelated condition. When clinical signs are present, they may include increased thirst and urination, increased heart rate, restlessness, and a distended abdomen. Hypertension (high blood pressure) is also common.

Diagnosis is often made based on clinical signs, presence of hypertension, and the finding of an adrenal mass on ultrasound examination.

Treatment involves surgically removing the adrenal tumor and managing the hypertension. The prognosis of dogs with pheochromocytoma is generally guarded, but some can be cured.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about pheochromocytoma on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about pheochromocytoma on our blog for veterinary professionals

13. Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism is a disorder of the gonads or sex glands (testes and ovaries) producing little or no sex hormones. In both males and females, hypogonadism can be primary (diseases of the gonad itself) or secondary to another disorder (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome). Male dogs with hypogonadism have testicular atrophy, characterized by small and soft testes. Hypogonadism decreases the animal’s tendency for marking and roaming, and lessens the aggressive behavior toward other dogs.

Most cases of hypogonadism in the dog result from castration. This condition is usually desired by the owner and requires no treatment. In the rare case in which treatment is desired, replacement testosterone can be given.

In the female dog, hypogonadism is more difficult to define because the sex hormones normally rise and fall during the phases of the estrus cycle. Like the male dog, the most common cause of hypogonadism in the female is ovariohysterectomy (spaying). This condition is usually desired by the owner and requires no treatment.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

14. Hypertension

Like people, dogs can and do develop high blood pressure (hypertension), especially with advancing age. There are numerous diseases in dogs that are may cause hypertension, including the following:

• Cushing’s syndrome (excess cortisol)

• Diabetes mellitus (inability to properly reduce blood sugar)

• Pheochromocytoma (an epinephrine secreting tumor of the adrenal gland)

• Chronic renal (kidney) failure: In one study, 93% of dogs with chronic renal failure and 61% of cats with chronic renal failure also had systemic hypertension.

In humans, high blood pressure is frequently considered “primary” (i.e., there is no underlying disease causing it). In dogs, primary hypertension is unusual; there is almost always another disease causing it. If routine screening does not identify the problem, more tests may be in order.

High blood pressure becomes an issue when a blood pressure to too high for the vessels carrying the blood. Imagine attaching a garden hose to a fire hydrant. The high pressure from the hydrant would cause the garden hose to explode. Hypertension is similar. When a blood vessel is too small for the pressure on it, it can “explode,” causing internal bleeding. Since the affected vessels are small, the bleeding may not be noticeable, but a lot of little bleeds and a lot of blood vessel destruction can create big problems long-term.

The retina of the eye is especially at risk; blindness is often the first sign of latent hypertension. The kidney can also be affected, as it relies on tiny, delicate vessels to filter toxins from the bloodstream. Not only is kidney disease an important cause of high blood pressure, but also it progresses far more rapidly in the presence of high blood pressure. In addition to hemorrhage, high blood pressure also increases the risk of embolism: tiny blood clots that form when blood flow is abnormal. These clots can lodge in dangerous locations, such as the brain.

Without obvious signs of hypertension, such as blindness, we discover hypertension through screening, as in humans. If your dog has one of the disorders commonly associated with hypertension, such as Cushing’s syndrome, your veterinarian should check its blood pressure. I recommend that even healthy dogs have their blood pressure checked annually, especially if they are over 9 to 10 years old. We check animal blood pressure similarly to how one check’s a human’s blood pressure; we use an inflatable cuff around the dog’s foot or foreleg, or at the base of the tail.

In addition to correcting the underlying cause of the hypertension, medication to actually lower blood pressure is often in order. Enalapril, a drug that acts to dilate blood vessels, is usually the first choice for dogs. It is typically given once or twice daily. Hypertensive dogs being treated with blood pressure medication should be rechecked every 2 to 4 months to keep their blood pressure in a healthy range.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

15. Obesity

By far, the most common explanation for an overweight pet is simple: lack of exercise and too much to eat. But what if you feed your dog sensibly, exercise adequately, and your dog still has a weight problem?

There could be a number of reasons your dog is still overweight, including hereditary, temperament, and overall activity level. However, a disease may be causing your dog to become overweight or obese. Hormonal diseases such as hypothyroidism and Cushing’s syndrome commonly cause weight gain. Hormone pills or tablets with cortisone-like drugs could also be contributing to the obesity.

Hypothyroidism is deficient thyroid hormone, and it causes alterations in cellular metabolism that affect the entire body. The dog may not feel like exercising and may gain weight because calories consumed are not matching calories expended. The weight gain then makes the dog feel like exercising even less. Hypothyroidism is usually inherited and a common genetic illness in dogs. Untreated hypothyroidism means a lower quality of life for your dog, but with the proper thyroid supplementation, this condition can be easily controlled, allowing your dog to enjoy a good quality of life.

Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism) is chronic excess of a glucocorticoid hormone, cortisol. This hormone is essential for functions such as maintaining blood glucose levels, metabolizing fats, keeping major organs functioning properly. There are different types of Cushing’s with many symptoms and causes, so it can sometimes be difficult to diagnose. Furthermore, its onset is slow, so its symptoms are often mistaken for signs of age. Cushing’s syndrome can cause reduced activity, change in appetite, and hair loss. Other symptoms include an increased thirst and urination, muscle weakness, and obesity. The cause of the Cushing’s syndrome determines the treatment, which is also influenced by the overall health of the dog.

Adequate exercise and proper diet are essential for all animals, but if your dog is overweight and you suspect an underlying disease, see a veterinarian for a thorough physical exam including laboratory tests.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

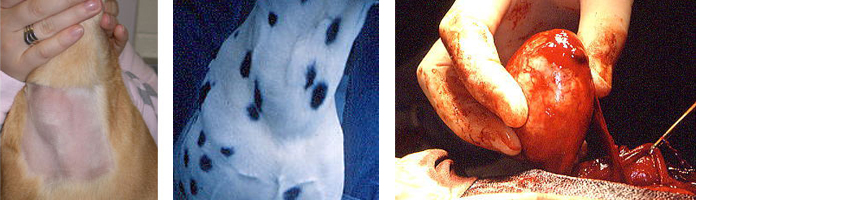

1. Acromegaly

Feline acromegaly is caused by a tumor of the pituitary gland that secretes growth hormone. Acromegaly usually affects cats 8 to 14 years of age and is more common in males. The pituitary tumors that cause acromegaly grow slowly and may be present for a few months before clinical signs appear.

Feline acromegaly causes diabetes mellitus relatively earlier in the course of this disease, so we expect to see the normal signs of diabetes, such as increased thirst, urination, appetite, and weight. Acromegaly produces severe” insulin resistance,” so most of these cats will require very large daily doses of insulin to control their diabetes. We always rule out acromegaly in the workup of all diabetic cats that have severe insulin resistance (on more than 8-10 units twice a day).

Other clinical signs will also develop in cats with acromegaly, addition to the severe diabetes. Because growth hormone is anabolic, parts of the cat’s body, such as the legs, paws, chin, and skull may become progressively larger with time. Internal organs, such as the heart, kidneys, and liver are become progressive larger over time. Finally, despite the uncontrolled or poorly controlled diabetes, acromegalic cats usually gain weight (remember that most diabetic cats experience some weight loss).

A tentative diagnosis of feline acromegaly is based upon compatible clinical features including insulin-resistant diabetes. The definitive diagnosis is based on a high blood growth hormone (GH) level with evidence of a pituitary tumor on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

While acromegaly can be treated symptomatically in the short-term, medicating the signs of acromegaly does not address the cause of the condition – the GH-secreting pituitary tumor. The long-term outlook for untreated cats is poor; most die of congestive heart failure, chronic kidney failure, or the growing pituitary tumor.

For the best long-term treatment results, external radiation therapy offers the greatest chance of success. This is the only available treatment that will destroy or shrink the size of the pituitary tumor and lower the high GH levels responsible for the cats’ clinical signs.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- -- Coming soon --

2. Diabetes insipidus

Despite its name, diabetes insipidus is not related to the more commonly known diabetes mellitus, and it does not involve insulin or sugar metabolism. The name comes from Greek, where it is roughly translated to mean the “excessive discharge of bland urine.” This is in contrast to diabetes mellitus, which can be translates as the “excessive discharge of sweet urine.”

Diabetes insipidus is caused by problems with antidiuretic hormone (ADH or vasopressin), a pituitary gland hormone responsible for maintaining the correct level of fluid in the body. Either the pituitary gland does not secrete enough of this hormone (called central diabetes insipidus), or the kidneys do not respond normally to the hormone (called nephrogenic diabetes insipidus).

Cats rarely develop diabetes insipidus. The cats that do develop diabetes insipidus are usually young, either kittens or young adults. Affected cats urinate large volumes and drink equally large amounts of water. Their urine is very dilute (clear), even if the cat is dehydrated. Normally, a dehydrated cat produces concentrated (dark) urine.

Increased urination may be controlled using desmopressin acetate, a drug that acts in a way similar to antidiuretic hormone. Water should not be restricted. Treatment is usually life-long.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about diabetes insipidus on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about diabetes insipidus on our blog for veterinary professionals

3. Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is a disorder in which the blood levels of two thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, are too high. It is caused by a tumor of the thyroid gland that produces excess hormone. Hyperthyroidism usually affects middle-aged and older cats. Although most cats have a benign thyroid tumor, a few cats will develop thyroid cancer; thyroid carcinoma is more common in cats treated for many months with an antithyroid drug, which blocks thyroid hormone production from the tumor but allows the tumor to grow and transform into a cancer.

The excess T3 and T4 increase the cat’s metabolic rate, producing a variety of signs. The most common signs include weight loss, excessive appetite, hyperexcitability, increased thirst and urination, vomiting, diarrhea, and increased fecal volume. Cardiovascular signs include increased heart rate, murmurs, shortness of breath, an enlarged heart, and congestive heart failure. Rarely, hyperthyroid cats have a reduced appetite, lethargy, and depression.

Veterinarians diagnose hyperthyroidism based on the cat’s history, clinical signs, and physical examination finding. They then confirm the diagnosis with one or more specific blood tests that measure thyroid hormone levels.

Veterinarians treat hyperthyroidism by three main methods: radioactive iodine (radioiodine, I-131) therapy, surgically removing the thyroid gland, or administering antithyroid drugs for the remainder of the cat’s life. Experts consider radioiodine the best treatment; it is simple, effective, and safe. The radioactive iodine concentrates within the thyroid tumor, where it irradiates and destroys the overactive thyroid tissue without affecting other tissues.

Surgically removing the thyroid gland is also effective. If the tumor affects only one side of the gland, only that half is removed and the cat will likely not require synthetic thyroid hormone supplements. If the tumor affects both sides of the gland (the case in 70% of hyperthyroid cats), the entire gland must be removed and the cat will require synthetic thyroid hormone after surgery. Unlike radioiodine therapy, surgery has complications. The main complication is that the parathyroid glands, which are located on top of or within the thyroid gland, can be injured or accidentally removed during surgery causing hypoparathyroidism. In this case, the cat will also require calcium and vitamin D supplements after surgery.

Daily treatment with methimazole or carbimazole, two similar antithyroid drugs, blocks the production of thyroid hormone. Both antithyroid drugs have several common adverse effects. These effects usually develop within the first 3 months, so your veterinarian should perform laboratory blood tests frequently (every 2-4 weeks) during this initial period. These blood tests will also help your veterinarian to adjust the methimazole dose such that it maintains normal thyroid hormone levels. After this initial period, your veterinarian will usually measure the thyroid hormone level every 3-6 months to monitor its effectiveness. Most cats need higher daily dosages over time, as the thyroid tumor continues to grow.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hyperthyroidism on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hyperthyroidism on our blog for veterinary professionals

4. Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is the condition where the thyroid gland does not produce enough of the thyroid hormones T3 and T4. When levels of these hormones are low, it slows metabolism.

Naturally occurring hypothyroidism is extremely rare in cats. When it does occur, it is most common in young cats that are born with the disorder.

In older cats, hypothyroidism is usually caused as a complication of treatment for hyperthyroidism. Hypothyroidism may develop after surgically removing a thyroid tumor, destroying it with radioiodine, or by administering antithyroid drugs as a treatment for hyperthyroidism.

Because deficient thyroid hormone affects the function of all organ systems, the signs of hypothyroidism vary. In cats, signs include lethargy, loss of appetite, hair loss, low body temperature, and occasionally decreased heart rate. Obesity may develop, especially in older cats that become hypothyroid after treatment of hyperthyroidism. In cats that are born with hypothyroidism (or that develop it at a young age), signs include dwarfing, severe lethargy, mental dullness, constipation, and decreased heart rate.

To accurately diagnose hypothyroidism, one must first closely evaluate the cat’s clinical signs and routine laboratory tests to rule out other diseases that affect thyroid hormone testing. The veterinarian must confirm the diagnosis using one more specific thyroid function tests. These tests may include serum total T4, free T4, or TSH levels. In some cases, a TSH stimulation test or thyroid imaging (scintigraphy) is necessary for diagnosis.

Hypothyroidism is easily treatable; it only requires synthetic thyroid hormone supplements. The success of treatment can be measured by the amount of improvement in clinical signs. Your veterinarian will have to monitor the thyroid hormone level to determine whether the thyroid hormone supplement dose is correct. Once the dose has been stabilized, thyroid hormone levels are usually checked once or twice a year. Treatment is generally life-long, but the prognosis is excellent.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypothyroidism on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypothyroidism on our blog for veterinary professionals

5. Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia is an abnormally high level of calcium in the blood. The signs associated with this condition depend on how high the calcium level is, how quickly it develops, and how long it lasts. The most common signs are increased thirst and urination. As the disease progresses, signs may include reduced appetite, vomiting, constipation, weakness, depression, muscle twitching, and seizures.

In cats, the two most common causes for hypercalcemia are idiopathic hypercalcemia and chronic kidney disease. We do not yet know what causes idiopathic hypercalcemia, but it may be related to diet. Rarely, a parathyroid tumor (hyperparathyroidism), cancer, and vitamin D overdose can cause hypercalcemia. (See Table for descriptions of some causes of hypercalcemia and their treatment.)

Hypercalcemia is treated by identifying and treating the condition that is causing it. However, the cause may not always be apparent. To lower the calcium level in the blood, your cat may require supportive therapy, including fluids, diuretics (“water pills”), sodium bicarbonate, and glucocorticoids.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypercalcemia on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypercalcemia on our blog for veterinary professionals

6. Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is an abnormally low level of calcium in the blood, leading to twitching, muscle tremors, and seizures.

A major cause of hypocalcemia is surgical removal or damage to the parathyroid glands (either as part of treatment for hyperparathyroidism or hyperthyroidism), which causes hypoparathyroidism (low parathyroid levels). Naturally occurring hypoparathyroidism is very rare in cats.

Other causes of hypocalcemia include kidney disease (renal failure) and calcium imbalance in nursing females.

Hypocalcemia causes the major signs of hypoparathyroidism by increasing the sensitivity, or excitability, of the nervous system. Common signs include muscle tremors and twitches, muscle contraction, and generalized convulsions. Diagnosis is based on history, clinical signs, low calcium and high phosphorous levels, and a low serum parathyroid hormone level. Other causes of hypocalcemia must also be eliminated.

The goal of treatment is not only to return the blood calcium level to normal, but also to eliminate the underlying cause of the hypocalcemia. Dietary calcium and vitamin D supplements help for the long-term. If a cat is having muscle spasms or seizures because of low blood calcium levels, immediate treatment with intravenous calcium is needed.

Chronic kidney failure is probably the most common cause of hypocalcemia. However, the hypocalcemia that occurs with kidney failure does not produce the nervous system signs that hypoparathyroidism does. Treatment for chronic kidney disease and associated hypocalcemia includes special renal diets that help lower the phosphate concentration in the blood.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about hypocalcemia on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypocalcemia on our blog for veterinary professionals

7. Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus (often called simply diabetes) is a disorder in which blood sugar levels are too high. In cats, either a deficiency of insulin or a resistance to insulin causes the diabetes. A number of mechanisms are responsible for decreased insulin secretion or resistance, but most involve destroying islet cells, the cells of the pancreas that produce insulin. In many cats with diabetes, a protein called amyloid collects in and damages the islet cells. Obesity also increases the risk of insulin resistance in cats.

During digestion, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose (a simple sugar), which is absorbed into the bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, glucose must enter the body’s cells in order to be used for energy. Insulin signals the body’s cells to absorb glucose from the blood.

A lack of insulin (or insulin resistance) creates two dangerous conditions. First, the body’s cells cannot absorb glucose without insulin; they begin to starve despite the abundant glucose. Second, because the body’s cells do not absorb glucose, the blood glucose level remains dangerously high. This excess glucose is eventually excreted from the body through the kidneys. As the glucose passes through the kidneys into the urine, it pulls water with it by diffusion. This causes increased urination, which leads to increased thirst.

With its cells starving for energy, the body begins to break down its protein, stored starches, and fat. In severe diabetes, muscle is broken down, carbohydrate stores are used up, and weakness and weight loss occur. As fat is broken down, substances called ketones are released into the bloodstream where they can eventually cause diabetic ketoacidosis, a severe complication of unregulated diabetes.

Diabetes can develop in cats of any breed, age or gender. However, older, overweight, and neutered male cats are predisposed to developing this disorder. Diabetes often develops gradually, and many owners may not notice the signs at first. Common signs include increased thirst and urination, increased appetite, weight loss, recurrent infections, and an enlarged liver.

Veterinarians diagnose diabetes when animals have high levels of sugar in the blood and urine after fasting. In cats, the blood sugar level commonly increases under stress, such as when drawing a blood sample, and multiple evaluations may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

To successfully manage diabetes, you must understand the disease and take daily care of your cat. Treatment involves a combination of weight loss (if obese), diet, and insulin injections generally twice daily. In some cats, oral medications can be used instead of insulin injections. Periodic reevaluation is necessary to ensure that the disease is being controlled. Based on these reevaluations, you may have to change your cat’s treatment regimen over time.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about diabetes mellitus on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about diabetes mellitus on our blog for veterinary professionals

8. Pancreatic insulin-secreting tumor (insulinoma)

An insulinoma is a tumor of the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas (i.e., the pancreatic islet cells), which secretes insulin in large volumes. Insulinomas are not common in cats.

Excess insulin secretion produces low blood sugar concentrations (hypoglycemia). Initially, signs may include weakness, fatigue after exercise, muscle twitching, lack of coordination, confusion, and changes of temperament. When hypoglycemia is severe, periodic seizures may occur.

Clinical signs occur only infrequently when the disease first begins. However, they become more frequent and last longer as the disease progresses. Signs resolve quickly after glucose treatment. Repeated episodes of prolonged and severe low blood sugar can result in irreversible brain damage.

Diagnosis is based on a history of periodic weakness, collapse, or seizures, along with tests indicating low blood sugar.

Removing the tumor surgically can correct the low blood sugar and nervous system signs unless it has already caused permanent damage. However, if the tumor has already spread (metastasis is common), blood sugar levels may remain low after surgery. While insulinomas are often malignant, they do not appear to be as aggressive in cats as they are in dogs. We can often improve these cats’ quality of life by modifying their diet and administering medications to increase their blood glucose level.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about insulinoma on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about insulinoma on our blog for veterinary professionals

9. Cushing’s syndrome (Hyperadrenocorticism)

Cushing’s syndrome, (hyperadrenocorticism), is a disorder associated with chronic excess of an adrenal cortex hormone, cortisol. Cushing’s syndrome is rare in cats. In most affected cats, the cause is a pituitary tumor, although an overactive pituitary gland or tumors of the adrenal gland itself are also possible causes.

Cushing's syndrome occurs most commonly in middle-aged or older cats; although both sexes are affected, female cats are more susceptible. The most common clinical signs of feline hyperadrenocorticism are polydipsia (increased drinking), polyuria (increased urination), and polyphagia (increased eating). All of these signs are observed because diabetes mellitus often occurs concurrently with feline Cushing’s syndrome. Therefore, polyuria and polydipsia develop as a result of hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and glycosuria (sugar in the urine) rather than from the excess cortisol levels per se.

Cushing’s syndrome also causes dermatologic signs, most notably extremely fragile, thin, infected, and easily bruised skin ("feline fragile skin syndrome"). These skin problems constitute the second most common set of clinical signs in cats with hyperadrenocorticism (second to polydipsia, polyuria, and polyphagia). Afflicted cats may also have an unkempt hair coat, patchy, and asymmetrical hair loss, muscle wasting, a potbelly (from enlarged liver), and pigmented skin. Some of these cats may appear listless or depressed because of muscle weakness or a large pituitary mass.

Hyperadrenocorticism is remarkably debilitating in cats. Although therapy is difficult and the prognosis is guarded, we usually attempt to control Cushing’s syndrome in cats in order to improve quality of life. Our best results have come from removing one adrenal gland in cats with an adrenal tumor, or both adrenal glands with pituitary-dependent Cushing’s disease. Recently, we have also had success using medical treatment with trilostane.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about Cushing's syndrome on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hyperadrenocorticism on our blog for veterinary professionals

10. Addison’s disease (Hypoadrencorticism )

Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism) is a disorder in which the adrenal gland does not produce sufficient hormones. It is extremely rare in cats.

The cause of feline Addison’s disease is usually not known, but most cats likely have an autoimmune condition where the body destroys part of the adrenal cortex. Rarely, infiltrative conditions such as lymphoma can metastasis to and destroy the adrenal gland to cause Addison’s disease. Finally, surgical removal of the adrenal glands for treatment of feline Cushing’s syndrome will lead to Addison’s disease.

With complete adrenocortical destruction, the cat develops both cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies. Aldosterone is the main mineralocorticoid hormone, and it affects the levels of potassium, sodium, and chloride in the blood. Low levels of aldosterone cause potassium to gradually build up in the blood and, in severe cases, cause the heart to slow down or beat irregularly. Some cats have such a slow heart rate (50 beats per minute or lower) that they can become weak or go into shock.

Signs of Addison’s disease include repeated episodes of vomiting and diarrhea, loss of appetite, dehydration, and gradual, but severe, weight loss. Because the clinical signs of Addison’s disease are vague and nonspecific, it can be difficult to diagnose in the earlier stages of disease. Therefore, severe consequences, such as shock and evidence of kidney failure, can develop suddenly in some cats.

A veterinarian may suspect Addison’s disease based on the cat’s history, clinical signs, and certain laboratory abnormalities, such as low serum sodium and high potassium concentrations. However, one must specifically evaluate adrenal function to document low cortisol levels to definitively diagnose Addison’s disease.

Untreated, Addison’s disease can lead to an adrenal crisis. An adrenal crisis is a medical emergency that requires intravenous fluids to restore the body’s levels of fluids, salts, and sugar to normal. Once stabilized, the cat can then be treated with hormone replacement therapy (either orally or by injection). With proper treatment, the long-term prognosis is excellent.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about Addison's disease on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hypoadrenocorticism on our blog for veterinary professionals

11. Conn’s syndrome (Hyperaldosteronism)

Conn’s syndrome (hyperaldosteronism) is a disorder in which the adrenal glands produce excess aldosterone. Aldosterone is the major mineralocorticoid secreted by the adrenal cortex and is responsible for regulating sodium and potassium (and with them, blood volume and acid-base balance). This disorder results in hypertension and/or hypokalemia (low blood potassium). Both of these conditions have their own significant clinical effects.

Conn’s syndrome is relatively rare and mainly affects older cats. About half of cats with Conn’s syndrome have a benign adrenal adenoma. Most of the remaining cats have a malignant adrenal carcinoma. However, there are also less common, nontumorous forms of Conn syndrome where both adrenal glands are affected (i.e., bilateral adrenal hyperplasia).

Common signs include generalized weakness (sometimes episodic), lethargy, depression, stiffness, muscle pain, increased thirst and urination, and blindness. Physical examination findings might include neck weakness, hypertension, and ocular changes, including retinal detachment or hemorrhage into the back of the eye.

Cats with Conn’s syndrome are commonly hypokalemic (low blood potassium level). Many affected cats are also hypertensive. Profound hypokalemia together with an inappropriately high plasma aldosterone concentration provides a definitive diagnosis of Conn’s syndrome. An abdominal ultrasound can be used to image each adrenal gland for evidence of adrenal enlargement or adrenal tumor.

Initial treatment of cats with Conn’s syndrome includes supplementation with potassium and correction of dehydration. Drugs that block the actions of aldosterone are also commonly used. Surgical adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice in most cats with Conn’s syndrome that do not have evidence of metastatic disease. For those cats which have adrenal disease on both glands, metastatic disease, or whose owners have declined surgery, medical management can sometimes be continued indefinitely.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about Conn's syndrome on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about hyperaldosteronism on our blog for veterinary professionals

12. Pheochromocytoma

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal medulla that secretes epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline), or both. Often, there are no clinical signs, and the tumor is found by chance while performing an abdominal ultrasound for the workup for an unrelated condition. When clinical signs are present, they may include increased thirst and urination, increased heart rate, restlessness, and a distended abdomen. Hypertension (high blood pressure) is also common.

Diagnosis is often made based on clinical signs, presence of hypertension, and the finding of an adrenal mass on ultrasound examination.

Treatment involves surgically removing the adrenal tumor and managing the hypertension. The prognosis of cats with pheochromocytoma is generally guarded, but some can be cured.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

- Posts about pheochromocytoma on our blog for pet owners

- Posts about pheochromocytoma on our blog for veterinary professionals

13. Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism is a disorder of the gonads or sex glands (testes and ovaries) producing little or no sex hormones. In both males and females, hypogonadism can be primary (diseases of the gonad itself) or secondary to another disorder (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome). Male cats with hypogonadism have testicular atrophy, characterized by small and soft testes. Hypogonadism decreases the animal’s tendency for marking and roaming, and lessens the aggressive behavior toward other cats.

Most cases of hypogonadism in the cat result from castration. This condition is usually desired by the owner and requires no treatment. In the rare case in which treatment is desired, replacement testosterone can be given.

In the female cat, hypogonadism is more difficult to define because the sex hormones normally rise and fall during the phases of the estrus cycle. Like the male cat, the most common cause of hypogonadism in the female is ovariohysterectomy (spaying). This condition is usually desired by the owner and requires no treatment.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

14. Hypertension

Like people, cats can and do develop high blood pressure (hypertension), especially with advancing age. There are numerous diseases in cats that are may cause hypertension, including the following:

• Hyperthyroidism: In one study, 87% of cats with untreated hyperthyroidism had systemic hypertension

• Cushing's disease (an adrenal cortisone excess)

• Diabetes mellitus (inability to properly reduce blood sugar)

• Acromegaly (growth hormone excess)

• Conn’s syndrome (an aldosterone-secreting tumor of the adrenal gland)

• Chronic renal (kidney) failure: In one study, 61% of cats with chronic renal failure also had systemic hypertension

In humans, high blood pressure is frequently considered “primary” (i.e., there is no underlying disease causing it). In cats, primary hypertension is unusual; there is almost always another disease causing it. If routine screening does not identify the problem, more tests may be in order.

High blood pressure becomes an issue when a blood pressure to too high for the vessels carrying the blood. Imagine attaching a garden hose to a fire hydrant. The high pressure from the hydrant would cause the garden hose to explode. Hypertension is similar. When a blood vessel is too small for the pressure on it, it can “explode,” causing internal bleeding. Since the affected vessels are small, the bleeding may not be noticeable, but a lot of little bleeds and a lot of blood vessel destruction can create big problems long-term.

The retina of the eye is especially at risk; blindness is often the first sign of latent hypertension. The kidney can also be affected, as it relies on tiny, delicate vessels to filter toxins from the bloodstream. Not only is kidney disease an important cause of high blood pressure, but also it progresses far more rapidly in the presence of high blood pressure. In addition to hemorrhage, high blood pressure also increases the risk of embolism: tiny blood clots that form when blood flow is abnormal. These clots can lodge in dangerous locations, such as the brain.

Without obvious signs of hypertension, such as blindness, we discover hypertension through screening, as in humans. If your cat has one of the disorders commonly associated with hypertension, such as hyperthyroidism or Conn’s syndrome, your veterinarian should check its blood pressure. I recommend that even healthy cats have their blood pressure checked annually, especially if they are over 11 to 12 years old. We check animal blood pressure similarly to how one check’s a human’s blood pressure; we use an inflatable cuff around the cat’s foot or foreleg, or at the base of the tail.

In addition to correcting the underlying cause of the hypertension, medication to actually lower blood pressure is often in order. Amlodipine, a drug that acts to dilate blood vessels, is usually the first choice for cats. It is typically given once or twice daily. Hypertensive cats being treated with blood pressure medication should be rechecked every 2 to 4 months to keep their blood pressure in a healthy range.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

15. Obesity

There are more cats than dogs in the USA at this time, and 40 percent of those cats are considered to be obese! Because of this, our cats are at risk for a number of obesity-related disorders. Obesity can predispose a cat to diabetes, hepatic lipidosis (fat accumulation in the liver), and arthritis. Cats that are overweight may also experience difficulty breathing or walking or they may be unable to tolerate heat or exercise.

Any cat that is overweight should have a physical exam performed, including an accurate measure of body weight and an assessment of body condition score. A historical review of changes in your cat's body weight is often helpful in establishing a pattern of weight gain and may help identify a particular event or change in environment that relates to the increase in body weight.

Routine blood work including a complete blood cell count, serum profile and urinalysis are necessary to determine if there is an underlying disease (such as a diabetes, thyroid or adrenal disease). If the results of these tests indicate a problem, additional tests are warranted to specifically identify the condition before starting a weight loss program.

Assessment of your cat's current daily intake of all food, treats, snacks, table foods and exercise schedule is important in the development of a successful weight loss program. Clearly if the calculated caloric intake exceeds the calculated daily energy requirement of the cat at an ideal body weight, then excessive caloric intake is the cause of the obesity.

Other causes of obesity are due to an altered energy metabolism. Some diseases and conditions can contribute to obesity. The most common of these in cats is diabetes, but hypothyroidism and Cushing's disease can also contribute to obesity in cats.

To learn more about the diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, please read:

Polydipsia and polyuria (increased thirst and urination)

Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes insipidus

Hyperparathyroidism and other causes of high blood calcium (hypercalcemia)

Weight loss

Diabetes mellitus

Hyperthyroidism

Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism)

Episodic weakness

Pancreatic insulin-secreting tumor (insulinoma)

Hypoadrenocorticism

Conn’s syndrome (hyperaldosteronism)

Hypoparathyroidism and other causes for low blood calcium (hypocalcemia)

Weight gain

Hypothyroidism

Diabetes mellitus (especially in cats)

Pancreatic insulin-secreting tumor (insulinoma)

Acromegaly

Hair thinning or hair loss

Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

Atypical Cushing’s (adrenal sex steroid excess)

Hypothyroidism

Pituitary dwarfism (growth hormone deficiency)

Gastrointestinal signs

Diabetes mellitus

Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism)

Hyperthyroidism

Hypoparathyroidism

Infertility/reproductive disease

Hypothyroidism

Hypogonadism

Pituitary dwarfism (growth hormone deficiency)

Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

Liver enzyme elevations

Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism)

Atypical Cushing’s (adrenal sex steroid excess)

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperlipidemia

Hypothyroidism

Hyperthyroidism

Diabetes mellitus

Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism)

Vision loss and blindness

Diabetes mellitus (especially in dogs)

Conn’s syndrome (hyperaldosteronism)

Hypertension (secondary to endocrine disorder such as acromegaly)

Acromegaly

A disorder associated with excessive growth of bone and soft tissue in the adult, resulting from the excess growth hormone (GH) secretion by the pituitary gland. Common disorder in cats; almost always caused by a GH-secreting pituitary adenoma.

ACTH

see Adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

A hormone produced by the pituitary gland that stimulates the secretion of cortisone and other hormones by the adrenal cortex. Abbreviated as ACTH, and synonymous with the term corticotrophin.

Addison’s disease

A disease caused by partial or total failure of adrenocortical function (the function of the adrenal cortex), characterized by poor appetite, weight loss, weakness, and vomiting. Also called hypoadrenocorticism or adrenocortical insufficiency.

Adenoma

A benign (non-cancerous) tumor, such as a thyroid or pituitary adenoma.

Adrenalectomy

An operation that removes one or both adrenal glands.

Adrenaline

See epinephrine.

Adrenocortical insufficiency

See Addison’s disease.

Adrenal cortex

The outer layer of the adrenal gland that secretes hormones, including cortisol and aldosterone, which are vital to the body.

Adrenal glands

The two adrenal glands are located on the top of each kidney. Each gland consists of a medulla (the center of the gland), surrounded by the cortex (outer core).

Adrenal medulla

The inner portion of the adrenal gland that secretes the catecholamine hormones adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norephinephrine).

Aldosterone

A hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex that affects blood pressure and sodium and potassium balance. See mineralocortioids.

ADH

See Antidiuretic hormone.

Amlodipine

A drug used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure). The trade name is Norvasc.

Androgens

Male sex hormones secreted by the gonads (testes). Small amounts are also secreted by the adrenal cortex.

Antidiuretic hormone

A hormone secreted by the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland that constricts blood vessels, raises blood pressure, and reduces urination. Abbreviated as ADH; also called vasopressin. ADH deficiency leads to the syndrome of diabetes insipidus.

Antithyroid drugs

Medications that reduce the thyroid gland's ability to produce thyroid hormone. The two main antithyroid drugs used in veterinary medicine are methimazole and carbimazole.

Benazepril

A drug used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure) and renal (kidney) protein loss. The trade names for the drug include Lotensin or Fortekor.

Benign

Non-cancerous.

Beta-blocking drugs

Medications that help alleviate the signs (nervousness, rapid heart rate) caused by excess T4 and T3 (see hyperthyroidism). These drugs act by blocking the effect of the catecholamines.

Calcitonin

A hormone secreted by the thyroid gland which controls the levels of calcium and phosphorous in the blood.

Catecholamines

see epinephrine and norepinephrine.

Carbimazole

An antithyroid medication used to treat hyperthyroidism.

CT Scan / CAT Scan

See computed tomography.

Computed tomography

A non-invasive procedure that takes cross-sectional images of the brain or other internal organs to detect abnormalities that may not show up on a routine X-ray.

Conn’s syndrome

A syndrome caused by an increased secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal gland (usually an adrenal). Disorder is characterized by high blood pressure and low blood potassium levels; weakness and blindness are common signs. Also called hyperaldosteronism.

Corticosteroids

Hormones produced by the adrenal cortex. The corticosteroids include cortisol (hydrocortisone), aldosterorone, and the adrenal sex steroids.

Corticotropin

See ACTH and adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Cortisol

See hydrocortisone.

Cushing’s syndrome

A syndrome caused by an increased secretion of cortisol from a tumor of the adrenal cortex or from an ACTH-secreting lesion in the pituitary gland. Also, can occur by excessive intake of glucocorticoids. Disorder is characterized by increase thirst and urination, enlarged abdomen, and hair loss on the trunk. Synonymous with the term hyperadrenocorticism.

Desiccated thyroid

A crude preparation made of animal thyroid glands. It was the first available source of thyroid hormone (T4). Because it is difficult to absorb and may contain impurities, desiccated thyroid preparations are no longer widely used.

Desmopressin

A synthetic analogue of antidiuretic hormone (ADH or vasopressin) used as a drug to treat central diabetes insipidus. The common trade name for desmopressin is DDAVP.

Diabetes mellitus

A disease caused by partial or total failure of insulin secretion from the pancreas. This causes the body to metabolize carbohydrates, fats, and proteins abnormally. The disorder is characterized by increased sugar levels in the blood and urine, excessive thirst, frequent urination, and wasting. Unrelated to diabetes insipidus.

Diabetes insipidus

A chronic metabolic disorder characterized by intense thirst and excessive urination. It is caused by problems with antidiuretic hormone, a pituitary hormone responsible for maintaining hydration. Either the pituitary gland does not secrete enough of this hormone (called central diabetes insipidus), or the kidneys do not respond normally to the hormone (called nephrogenic diabetes insipidus).

Enalapril

A drug used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure). The trade names for the drug include Enacard or Vasotec.

Endocrine

Relating to endocrine glands or the hormones secreted by them.

Epinephrine

Hormone secreted by the medulla (central part) of the adrenal glands. Functions in the “fight or flight” response. Commonly known as “adrenaline.”

Estrogen

A hormone secreted by the ovaries that affects many aspects of the female body, including menstrual cycles and pregnancy. Small amounts of estrogen also secreted by adrenal cortex.

External radiation therapy

A type of radiation therapy that directs beams of high-energy X-rays or particles from outside of the patient’s body to kill cancer cells. During this type of radiation, high-energy beams come from special machines, such as linear accelerators (LINAC) or cobalt machines.

Felimazole

Trade name for methimazole, an antithyroid drug.

Free T4

Free thyroxine, a thyroid function test. Measures the non-protein bond fraction of T4 in the circulation.

Glucocorticoids

Any of a group of adrenocortical hormones (eg, cortisol, cortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone) that regulate carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism. At higher doses, these hormones can have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties.

Glucagon

A protein hormone secreted by the pancreas that acts on the liver to stimulate glucose production and raise the blood sugar level.

Goiter

Enlargement of the thyroid gland for any reason. Goiter can be diffuse (general enlargement) or nodular (asymmetric enlargement). In animals, goiter is usually caused by a thyroid tumor, but may be seen in some types of congenital hypothyroidism.

Gonads

Ovaries or testes.

Gonadotropins

Hormones produced by the pituitary gland that regulate gonadal function. There are two gonadotropins

luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Graves' disease

A form of hyperthyroidism caused by an overactive, diffuse goiter that is often associated with exophthalmos (bulging eyes). This form of hyperthyroidism does not occur in dogs and cats.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis

Inflammation of the thyroid gland. Typically leads to a form of hypothyroidism.

Hormone

A chemical produced by an endocrine gland and released into the blood. It travels to other organs or parts of the body where it produces its effect.

Hydrocortisone

A hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex that affects metabolism and is necessary for life. Also called cortisol.

Hyper- (prefix)

Over; excess; high; above normal.

Hyperadrenocorticism

See Cushing’s syndrome.

Hyperaldosteronism

See Conn’s syndrome.

Hyperparathyroidism

Overproduction of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by a diseased parathyroid gland (usually a parathyroid tumor). The excess PTH causes hypercalcemia (calcium level that is too high).

Hyperthyroidism

Condition caused by excess thyroid hormone secretion associated with symptoms of increased metabolic rate. Common in cats, usually caused by benign thyroid adenoma.

Hypo- (prefix)

Under; deficient; low; below normal.

Hypoadrenocorticism

See Addison’s disease or Adrenocortical insufficiency.

Hypogonadism

Disorder associated with the sex glands (gonads) producing little or no sex hormones. In males, these glands are the testes; in females, they are the ovaries.

Hypoparathyroidism

Lack of parathyroid hormones which leads to hypocalcemia (low blood calcium). Hypocalcemia can cause muscle spasms, tetany, and seizures.

Hypothyroidism

Condition caused by deficient thyroid hormone secretion associated with symptoms of decreased metabolic rate. Common in dogs.

Hypothalamus

The portion of the brain, located just above the brain stem, which controls and regulates the pituitary gland.

Insulin

The hormone released by the pancreas to reduce high blood glucose. Deficiency of this hormone results in diabetes mellitus.

Insulinoma

An insulin-secreting tumor of the pancreas, leading to hypoglycemia (low blood glucose).

Intravenous

Introducing a sterile fluid into the bloodstream through a vein.

Iodine

A non-metallic element found in food. It is necessary for normal thyroid function and is routinely added to table salt.

Islets of Langerhans

Groups of pancreatic cells that produce insulin and glucagon, the hormones that regulate and maintain normal blood glucose levels.

Levothyroxine (L-T4)

Synthetic form of thyroxine (T4). Used in treatment of hypothyroidism.

Lysodren

The trade name for the drug mitotane, used to treat Cushing’s syndrome.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

A non-invasive procedure that creates two-dimensional images of internal organs, especially the brain and spinal cord, using magnetic fields. Commonly abbreviated as MRI.

Malignant

Cancerous.

Medulla

The central part of a gland (e.g., the adrenal medulla).

Metabolism

The use of calories (food energy) and oxygen to produce energy.

Methimazole

An antithyroid medication used to treat hyperthyroidism.

Mineralocorticoid

A group of steroid hormones made in the adrenal gland which act to regulate the balance of water and electrolytes in the body. The principal mineralocorticoid in dogs and cats is aldosterone.

Mitotane

A drug used to treat dogs with Cushing's syndrome.

MRI

See Magnetic resonance imaging.

Multi-nodular goiter

Enlarged thyroid gland with two or more nodules.

Myxedema

Specific form of cutaneous edema; often associated with severe hypothyroidism. Usually seen as mild to moderate swelling of the face and forehead, giving affected dogs a “tragic” facial expression.

Norepinephrine